- Windows Memory Management

- Windows Memory Architecture Overview

- Windows Server Memory Architecture

- Windows Ce 6.0 Memory Architecture

- Memory Architecture Pdf

- Windows Memory Architecture Pdf

Introduction

Each process started on x86 version of Windows uses a flat memory model that ranges from 0x00000000 – 0xFFFFFFFF. The lower half of the memory, 0x00000000 – 0x7FFFFFFF, is reserved for user space code.While the upper half of the memory, 0x80000000 – 0xFFFFFFFF, is reserved for the kernel code. The Windows operating system also doesn’t use the segmentation (well actually it does, because it has to), but the segment table contains segment descriptors that use the entire linear address space. There are four segments, two for user and two for kernel mode, which describe the data and code for each of the modes. But all of the descriptors actually contain the same linear address space. This means they all point to the same segment in memory that is 0xFFFFFFFF bits long, proving that there is no segmentation on Windows systems.

- Querying for whether Unified Memory Architecture (UMA) is supported can help determine how to handle some resources. A boolean, set by the driver, can be read from the D3D11FEATUREDATAD3D11OPTIONS2 structure to determine if the hardware supports UMA.

- Understanding Windows 10 Editions, Architectures and Builds. Determining Your Windows 10 Architecture. Some computers might be 64-bit capable but are limited by the amount of memory that.

Dec 23, 2010 The memory architecture used by an operating system is the most important key to understanding how the operating system does what it does. When you start working with a new operating system, many questions come to mind.

Let’s execute the “dg 0 30” command to display the first 7 segment descriptors that can be seen on the picture below:

Notice that the 0008, 0010, 0018 and 0020 all start at base address 0x00000000 and end at address 0xFFFFFFFF: They represent the data and code segments of user and kernel mode. This also proves that the segmentation is actually not used by the Windows system. Therefore we can use the terms”virtual address space” and “linear address space” interchangeably, because they are the same in this particular case. Because of this, when talking about user space code being loaded in the virtual address space from 0x00000000 to 0x7FFFFFFF, we’re actually talking about linear addresses. Those addresses are then sent into the paging unit to be translated into physical addresses. We’ve just determined that even though each process uses a flat memory model that spans the entire 4GB linear address space, it can only use half of it.This is because the other half is reserved for kernel code: the program can thus use, at most, 2GB of memory.

Every process has its own unique value in the CR3 register that points to the process’ page directory table. Because each process has its own page directory table that is used to translate the linear address to physical address, two processes can use the same linear address, while their physical address is different. Okay, so each program has its own address space reserved only for that process, but what about the kernel space? Actually, the kernel is loaded only once in memory and each program must use it. This is why each process needs appropriate pointers set-up that do just that. It means that the PDEs stored in the page directory of every process point to the same kernel page table.

We know that the kernel’s memory is protected by various mechanisms, so the user process can’t call it directly, but can call into the kernel by using special gates that only allow certain actions to be requested of kernel. Thus, we can’t simply tell a program to go into kernel mode and do whatever it pleases,because the code that does whatever we want is in user space. Therefore,the programs can only request a special action that’s already provided by a kernel’s code to do it for them. If we would like to run our own code in kernel memory, we must first find a way to pass the code to the kernel and stay there. One such example would be the installation of some driver that requires kernel privileges to be run,because it’s interacting more or less directly with the hardware component for which the driver has been written. The user processes can then use that driver’s functionality to request certain actions to be done: but only those that have been implemented in the driver itself. I hope I made it clear that the functionality run in kernel mode is limited to the functionality of the code loaded in kernel mode, and thus the code from user mode is not allowed to be executed with kernel privileges.

Let’s take a look at an example. On the Windows system being debugged by Windbg, I started Internet Explorer and Opera to analyze their memory space. After the programs have been started, I run the “!process 0 0” command to get the basic information about all the processes currently active on a system. The result of the command can be shown below where we’ve only listed the two processes in question (not all of them):

The DirBase element above is actually the value that gets stored in the CR3 register every time a context-switch to a particular process occurs. That value is used as a pointer to the page table directory that contains PDEs. The page directory table of process opera.exe is stored at physical address 0x094c01a0, while the page directory table of process IEXPLORE.EXE is stored at physical address 0x094c0200. Because the 0x00000000 to 0x7FFFFFFF linear address space is used by the program and not the kernel, the program will use the first half of the PDE entries in its page directory, while the kernel will use the second half. Since, if PAE is disabled, each program has 1024 PDE entries, 512 of them refer to user space memory, and the other 512 refer to kernel space memory.

The !process commands above have been used to get the pointer to the process’s EPROCESS structure in memory. With the .process command, we can set the context to the current process. This is mandatory step if we would like to run some other commands that require us to be in the process’s context in order to be run successfully. To switch to the context of the iexplore.exe process, we have to execute the “.process 81f799f8” command as can be seen below:

There was some warning message about forcedecodeuser not being enabled. The problem with this is that the context switch won’t occur to the requested process. To solve that we need to enable the forcedecodeuser with the “.cache forcedecodeuser” command. The output from that command can be seen on the picture below:

Notice that we’ve first enabled the forcedecodeuser, and then run the .process command to switch to the context of the iexplore.exe’s process? This time there was no error message and the context-switch actually occurred.

Notice that all the loaded DLLs that the program uses have been loaded in the user space (keep in mind that we didn’t present all the DLLs because the iexplore.exe uses too many of them to be presented in a sane manner). All the loaded DLLs also have their path displayed, which makes it very easy to find them on the hard drive. Let’s also present the second part of the output, which has long lines, so they can’t be presented here. Luckily the windbg has a “word wrap” functionality that can be enabled by right-clicking on the window and selecting “Word wrap” as can be seen below:

Notice that the “Word wrap” is enabled, which means that the lines will only be as long as the window’s width.If lines are longer they will be wrapped and put into the second line. Let’s now present the second half of the output from running the !peb command:

There are quite many information available on the picture above, like the address of the process heap, the process parameters, the command line used to invoke the program, the path where to search for DLLs, etc. Also all the environment variables of this process are shown, but only the first three are presented for clarity.

Let’s now download the Sysinternals Suite and run the vmmap tool, which will ask us to select a process when launching. We can see that on the picture below, we must select the IEXPLORE.EXE to view it’s memory:

The vmmon will then analyze the memory and present us with the statistics about which memory is used for heap, stack, data, etc. This can be seen on the picture below:

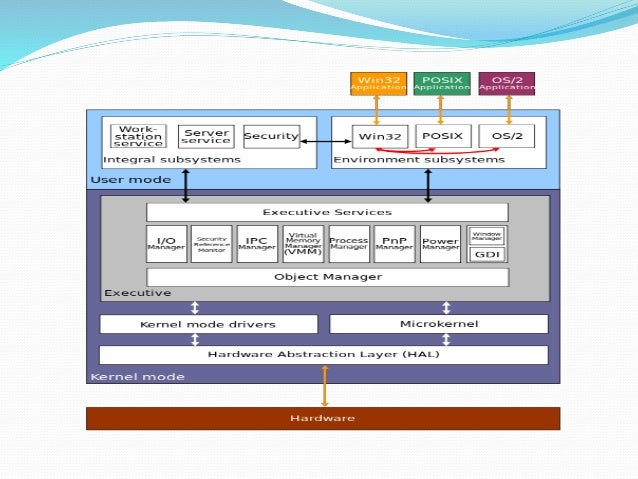

Windows Architecture

Let’s present a picture about Windows Architecture taken from [2]:

On the picture above we can see the HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer), which is the first abstraction layer that abstracts the hardware details from the operating system. The operating system can then call the same API functions and the HAL takes care of how they are actually executed on the underlying hardware. Every driver that is loaded in the kernel mode uses HAL to interact with the hardware components, so even the drivers don’t interact with hardware directly. The kernel drivers can interact with the hardware directly, but usually they don’t need to, since they can use HAL API to execute some action. The hardware abstraction layer’s API is provided with the hal.dll library file that is located in the C:WINDOWSsystem32 directory as can be seen below:

The rest of the system kernel components are provided by the following libraries and executables [3]:

- csrss.exe : manages user processes and threads

- win32k.sys : user and graphics device driver (GDI)

- kernel32.dll : access to resources like file system, devices, processes, threads and error handling in Windows systems

- advapi32.dll : access to windows registry, shutdown/restart the system, start/stop/create services, manage user accounts

- user32.dll : create and manage screen windows, buttons, scrollbars, receive mouse and keyboard input

- gdi32.dll : outputs graphical content to monitors, printers and other output devices

- comdlg32.dll : dialog boxes for opening and saving files, choosing color and font

- comctl32.dll : access to status bars, progress bars, tools, tabs

- shell32.dll : access the operating system shell

- netapi32.dll : access to networking functions

The programs can use Windows API (Win 32 API) to implement the needed actions. But the WinAPI uses the described DLL libraries underneath.

Right above the kernel mode is the user mode, where the most important library is ntdll.dll.Thatcan be used as an entry point into the kernel if some process needs services of the kernel.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how the user and kernel mode are separated and what each of those provide to the user. The kernel mode is used to provide services to the user mode applications. The kernel mode is capable of doing almost anything with the underlying system, but the most important thing is the existence of Win32 API that provides another abstraction layer over the underlying hardware components.

If you’re interested in knowing all of the system libraries that a kernel uses, you can run the “lm n” command in Windbg, which will list all of the libraries used by the kernel mode.

We can see that there are a lot of loaded libraries that kernel mode uses to provide services to the user application and to keep track of everything the operating system must do.

References:

[1] PankajGarg, Windows Memory Management, accessible at http://www.intellectualheaven.com/Articles/WinMM.pdf.

[2] HanyBarakat’s Technical Blog, accessible at http://blogs.msdn.com/b/hanybarakat/archive/2007/02/25/deeper-into-windows-architecture.aspx.

[3] Windows API, accessible at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windows_API.

/strong

-->Windows Virtual Memory Manager

The committed regions of address space are mapped to the available physical memory by the Windows Virtual Memory Manager (VMM).

For more information on the amount of physical memory supported by different operating systems, see the Windows documentation on Memory Limits for Windows Releases.

Virtual memory systems allow the over-commitment of physical memory, so that the ratio of virtual-to-physical memory can exceed 1:1. As a result, larger programs can run on computers with a variety of physical memory configurations. However, using significantly more virtual memory than the combined average working sets of all the processes can cause poor performance.

SQL Server Memory Architecture

SQL Server dynamically acquires and frees memory as required. Typically, an administrator does not have to specify how much memory should be allocated to SQL Server, although the option still exists and is required in some environments.

One of the primary design goals of all database software is to minimize disk I/O because disk reads and writes are among the most resource-intensive operations. SQL Server builds a buffer pool in memory to hold pages read from the database. Much of the code in SQL Server is dedicated to minimizing the number of physical reads and writes between the disk and the buffer pool. SQL Server tries to reach a balance between two goals:

- Keep the buffer pool from becoming so big that the entire system is low on memory.

- Minimize physical I/O to the database files by maximizing the size of the buffer pool.

Note

In a heavily loaded system, some large queries that require a large amount of memory to run cannot get the minimum amount of requested memory and receive a time-out error while waiting for memory resources. To resolve this, increase the query wait Option. For a parallel query, consider reducing the max degree of parallelism Option.

Note

In a heavily loaded system under memory pressure, queries with merge join, sort and bitmap in the query plan can drop the bitmap when the queries do not get the minimum required memory for the bitmap. This can affect the query performance and if the sorting process can not fit in memory, it can increase the usage of worktables in tempdb database, causing tempdb to grow. To resolve this problem add physical memory or tune the queries to use a different and faster query plan.

Providing the maximum amount of memory to SQL Server

By using AWE and the Locked Pages in Memory privilege, you can provide the following amounts of memory to the SQL Server Database Engine.

Note

The following table includes a column for 32-bit versions, which are no longer available.

| 32-bit 1 | 64-bit | |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional memory | All SQL Server editions. Up to process virtual address space limit: - 2 GB - 3 GB with /3gb boot parameter 2 - 4 GB on WOW64 3 | All SQL Server editions. Up to process virtual address space limit: - 7 TB with IA64 architecture (IA64 not supported in SQL Server 2012 (11.x) and above) - Operating system maximum with x64 architecture 4 |

| AWE mechanism (Allows SQL Server to go beyond the process virtual address space limit on 32-bit platform.) | SQL Server Standard, Enterprise, and Developer editions: Buffer pool is capable of accessing up to 64 GB of memory. | Not applicable 5 |

| Lock pages in memory operating system (OS) privilege (allows locking physical memory, preventing OS paging of the locked memory.) 6 | SQL Server Standard, Enterprise, and Developer editions: Required for SQL Server process to use AWE mechanism. Memory allocated through AWE mechanism cannot be paged out. Granting this privilege without enabling AWE has no effect on the server. | Only used when necessary, namely if there are signs that sqlservr process is being paged out. In this case, error 17890 will be reported in the Errorlog, resembling the following example: A significant part of sql server process memory has been paged out. This may result in a performance degradation. Duration: #### seconds. Working set (KB): ####, committed (KB): ####, memory utilization: ##%. |

1 32-bit versions are not available starting with SQL Server 2014 (12.x).

2 /3gb is an operating system boot parameter. For more information, visit the MSDN Library.

3 WOW64 (Windows on Windows 64) is a mode in which 32-bit SQL Server runs on a 64-bit operating system.

4 SQL Server Standard Edition supports up to 128 GB. SQL Server Enterprise Edition supports the operating system maximum.

5 Note that the sp_configure awe enabled option was present on 64-bit SQL Server, but it is ignored.

6 If lock pages in memory privilege (LPIM) is granted (either on 32-bit for AWE support or on 64-bit by itself), we recommend also setting max server memory. For more information on LPIM, refer to Server Memory Server Configuration Options

Windows Memory Management

Note

Older versions of SQL Server could run on a 32-bit operating system. Accessing more than 4 gigabytes (GB) of memory on a 32-bit operating system required Address Windowing Extensions (AWE) to manage the memory. This is not necessary when SQL Server is running on 64-bit operation systems. For more information about AWE, see Process Address Space and Managing Memory for Large Databases in the SQL Server 2008 documentation.

Changes to Memory Management starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x)

In earlier versions of SQL Server ( SQL Server 2005 (9.x), SQL Server 2008 and SQL Server 2008 R2), memory allocation was done using five different mechanisms:

- Single-Page Allocator (SPA), including only memory allocations that were less than, or equal to 8-KB in the SQL Server process. The max server memory (MB) and min server memory (MB) configuration options determined the limits of physical memory that the SPA consumed. THe buffer pool was simultaneously the mechanism for SPA, and the largest consumer of single-page allocations.

- Multi-Page Allocator (MPA), for memory allocations that request more than 8-KB.

- CLR Allocator, including the SQL CLR heaps and its global allocations that are created during CLR initialization.

- Memory allocations for thread stacks in the SQL Server process.

- Direct Windows allocations (DWA), for memory allocation requests made directly to Windows. These include Windows heap usage and direct virtual allocations made by modules that are loaded into the SQL Server process. Examples of such memory allocation requests include allocations from extended stored procedure DLLs, objects that are created by using Automation procedures (sp_OA calls), and allocations from linked server providers.

Starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x), Single-Page allocations, Multi-Page allocations and CLR allocations are all consolidated into a 'Any size' Page Allocator, and it's included in memory limits that are controlled by max server memory (MB) and min server memory (MB) configuration options. This change provided a more accurate sizing ability for all memory requirements that go through the SQL Server memory manager.

Important

Carefully review your current max server memory (MB) and min server memory (MB) configurations after you upgrade to SQL Server 2012 (11.x) through SQL Server 2017. This is because starting in SQL Server 2012 (11.x), such configurations now include and account for more memory allocations compared to earlier versions.These changes apply to both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of SQL Server 2012 (11.x) and SQL Server 2014 (12.x), and 64-bit versions of SQL Server 2016 (13.x) through SQL Server 2017.

The following table indicates whether a specific type of memory allocation is controlled by the max server memory (MB) and min server memory (MB) configuration options:

| Type of memory allocation | SQL Server 2005 (9.x), SQL Server 2008 and SQL Server 2008 R2 | Starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-page allocations | Yes | Yes, consolidated into 'any size' page allocations |

| Multi-page allocations | No | Yes, consolidated into 'any size' page allocations |

| CLR allocations | No | Yes |

| Thread stacks memory | No | No |

| Direct allocations from Windows | No | No |

Starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x), SQL Server might allocate more memory than the value specified in the max server memory setting. This behavior may occur when the Total Server Memory (KB) value has already reached the Target Server Memory (KB) setting (as specified by max server memory). If there is insufficient contiguous free memory to meet the demand of multi-page memory requests (more than 8 KB) because of memory fragmentation, SQL Server can perform over-commitment instead of rejecting the memory request.

As soon as this allocation is performed, the Resource Monitor background task starts to signal all memory consumers to release the allocated memory, and tries to bring the Total Server Memory (KB) value below the Target Server Memory (KB) specification. Therefore, SQL Server memory usage could briefly exceed the max server memory setting. In this situation, the Total Server Memory (KB) performance counter reading will exceed the max server memory and Target Server Memory (KB) settings.

This behavior is typically observed during the following operations:

Windows Memory Architecture Overview

- Large Columnstore index queries.

- Columnstore index (re)builds, which use large volumes of memory to perform Hash and Sort operations.

- Backup operations that require large memory buffers.

- Tracing operations that have to store large input parameters.

Changes to 'memory_to_reserve' starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x)

In earlier versions of SQL Server ( SQL Server 2005 (9.x), SQL Server 2008 and SQL Server 2008 R2), the SQL Server memory manager set aside a part of the process virtual address space (VAS) for use by the Multi-Page Allocator (MPA), CLR Allocator, memory allocations for thread stacks in the SQL Server process, and Direct Windows allocations (DWA). This part of the virtual address space is also known as 'Mem-To-Leave' or 'non-Buffer Pool' region.

The virtual address space that is reserved for these allocations is determined by the memory_to_reserve configuration option. The default value that SQL Server uses is 256 MB. To override the default value, use the SQL Server -g startup parameter. Refer to the documentation page on Database Engine Service Startup Options for information on the -g startup parameter.

Because starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x), the new 'any size' page allocator also handles allocations greater than 8 KB, the memory_to_reserve value does not include the multi-page allocations. Except for this change, everything else remains the same with this configuration option.

The following table indicates whether a specific type of memory allocation falls into the memory_to_reserve region of the virtual address space for the SQL Server process:

| Type of memory allocation | SQL Server 2005 (9.x), SQL Server 2008 and SQL Server 2008 R2 | Starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-page allocations | No | No, consolidated into 'any size' page allocations |

| Multi-page allocations | Yes | No, consolidated into 'any size' page allocations |

| CLR allocations | Yes | Yes |

| Thread stacks memory | Yes | Yes |

| Direct allocations from Windows | Yes | Yes |

Dynamic Memory Management

The default memory management behavior of the SQL Server Database Engine is to acquire as much memory as it needs without creating a memory shortage on the system. The SQL Server Database Engine does this by using the Memory Notification APIs in Microsoft Windows.

When SQL Server is using memory dynamically, it queries the system periodically to determine the amount of free memory. Maintaining this free memory prevents the operating system (OS) from paging. If less memory is free, SQL Server releases memory to the OS. If more memory is free, SQL Server may allocate more memory. SQL Server adds memory only when its workload requires more memory; a server at rest does not increase the size of its virtual address space.

Max server memory controls the SQL Server memory allocation, compile memory, all caches (including the buffer pool), query execution memory grants, lock manager memory, and CLR1 memory (essentially any memory clerk found in sys.dm_os_memory_clerks).

1 CLR memory is managed under max_server_memory allocations starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x).

The following query returns information about currently allocated memory:

Memory for thread stacks1, CLR2, extended procedure .dll files, the OLE DB providers referenced by distributed queries, automation objects referenced in Transact-SQL statements, and any memory allocated by a non SQL Server DLL are not controlled by max server memory.

1 Refer to the documentation page on how to Configure the max worker threads Server Configuration Option, for information on the calculated default worker threads for a given number of affinitized CPUs in the current host. SQL Server stack sizes are as follows:

| SQL Server Architecture | OS Architecture | Stack Size |

|---|---|---|

| x86 (32-bit) | x86 (32-bit) | 512 KB |

| x86 (32-bit) | x64 (64-bit) | 768 KB |

| x64 (64-bit) | x64 (64-bit) | 2048 KB |

| IA64 (Itanium) | IA64 (Itanium) | 4096 KB |

2 CLR memory is managed under max_server_memory allocations starting with SQL Server 2012 (11.x).

SQL Server uses the memory notification API QueryMemoryResourceNotification to determine when the SQL Server Memory Manager may allocate memory and release memory.

When SQL Server starts, it computes the size of virtual address space for the buffer pool based on a number of parameters such as amount of physical memory on the system, number of server threads and various startup parameters. SQL Server reserves the computed amount of its process virtual address space for the buffer pool, but it acquires (commits) only the required amount of physical memory for the current load.

The instance then continues to acquire memory as needed to support the workload. As more users connect and run queries, SQL Server acquires the additional physical memory on demand. A SQL Server instance continues to acquire physical memory until it either reaches its max server memory allocation target or the OS indicates there is no longer an excess of free memory; it frees memory when it has more than the min server memory setting, and the OS indicates that there is a shortage of free memory.

As other applications are started on a computer running an instance of SQL Server, they consume memory and the amount of free physical memory drops below the SQL Server target. The instance of SQL Server adjusts its memory consumption. If another application is stopped and more memory becomes available, the instance of SQL Server increases the size of its memory allocation. SQL Server can free and acquire several megabytes of memory each second, allowing it to quickly adjust to memory allocation changes.

Effects of min and max server memory

The min server memory and max server memory configuration options establish upper and lower limits to the amount of memory used by the buffer pool and other caches of the SQL Server Database Engine. The buffer pool does not immediately acquire the amount of memory specified in min server memory. The buffer pool starts with only the memory required to initialize. As the SQL Server Database Engine workload increases, it keeps acquiring the memory required to support the workload. The buffer pool does not free any of the acquired memory until it reaches the amount specified in min server memory. Once min server memory is reached, the buffer pool then uses the standard algorithm to acquire and free memory as needed. The only difference is that the buffer pool never drops its memory allocation below the level specified in min server memory, and never acquires more memory than the level specified in max server memory.

Note

SQL Server as a process acquires more memory than specified by max server memory option. Both internal and external components can allocate memory outside of the buffer pool, which consumes additional memory, but the memory allocated to the buffer pool usually still represents the largest portion of memory consumed by SQL Server.

The amount of memory acquired by the SQL Server Database Engine is entirely dependent on the workload placed on the instance. A SQL Server instance that is not processing many requests may never reach min server memory.

If the same value is specified for both min server memory and max server memory, then once the memory allocated to the SQL Server Database Engine reaches that value, the SQL Server Database Engine stops dynamically freeing and acquiring memory for the buffer pool.

If an instance of SQL Server is running on a computer where other applications are frequently stopped or started, the allocation and deallocation of memory by the instance of SQL Server may slow the startup times of other applications. Also, if SQL Server is one of several server applications running on a single computer, the system administrators may need to control the amount of memory allocated to SQL Server. In these cases, you can use the min server memory and max server memory options to control how much memory SQL Server can use. The min server memory and max server memory options are specified in megabytes. For more information, see Server Memory Configuration Options.

Memory used by SQL Server objects specifications

The following list describes the approximate amount of memory used by different objects in SQL Server. The amounts listed are estimates and can vary depending on the environment and how objects are created:

- Lock (as maintained by the Lock Manager): 64 bytes + 32 bytes per owner

- User connection: Approximately (3 * network_packet_size + 94 kb)

The network packet size is the size of the tabular data scheme (TDS) packets that are used to communicate between applications and the SQL Server Database Engine. The default packet size is 4 KB, and is controlled by the network packet size configuration option.

When multiple active result sets (MARS) are enabled, the user connection is approximately (3 + 3 * num_logical_connections) * network_packet_size + 94 KB

Effects of min memory per query

The min memory per query configuration option establishes the minimum amount of memory (in kilobytes) that will be allocated for the execution of a query. This is also known as the minimum memory grant. All queries must wait until the minimum memory requested can be secured, before execution can start, or until the value specified in the query wait server configuration option is exceeded. The wait type that is accumulated in this scenario is RESOURCE_SEMAPHORE.

Important

Do not set the min memory per query server configuration option too high, especially on very busy systems, because doing so could lead to:

- Increased competition for memory resources.

- Decreased concurrency by increasing the amount of memory for every single query, even if the required memory at runtime is lower that this configuration.

For recommendations on using this configuration, see Configure the min memory per query Server Configuration Option.

Memory grant considerations

For row mode execution, the initial memory grant cannot be exceeded under any condition. If more memory than the initial grant is needed to execute hash or sort operations, then these will spill to disk. A hash operation that spills is supported by a Workfile in TempDB, while a sort operation that spills is supported by a Worktable.

A spill that occurs during a Sort operation is known as a Sort Warning. Sort warnings indicate that sort operations do not fit into memory. This does not include sort operations involving the creation of indexes, only sort operations within a query (such as an ORDER BY clause used in a SELECT statement).

A spill that occurs during a hash operation is known as a Hash Warning. These occur when a hash recursion or cessation of hashing (hash bailout) has occurred during a hashing operation.

- Hash recursion occurs when the build input does not fit into available memory, resulting in the split of input into multiple partitions that are processed separately. If any of these partitions still do not fit into available memory, it is split into sub-partitions, which are also processed separately. This splitting process continues until each partition fits into available memory or until the maximum recursion level is reached.

- Hash bailout occurs when a hashing operation reaches its maximum recursion level and shifts to an alternate plan to process the remaining partitioned data. These events can cause reduced performance in your server.

For batch mode execution, the initial memory grant can dynamically increase up to a certain internal threshold by default. This dynamic memory grant mechanism is designed to allow memory resident execution of hash or sort operations running in batch mode. If these operations still do not fit into memory, then these will spill to disk.

For more information on execution modes, see the Query Processing Architecture Guide.

Buffer management

The primary purpose of a SQL Server database is to store and retrieve data, so intensive disk I/O is a core characteristic of the Database Engine. And because disk I/O operations can consume many resources and take a relatively long time to finish, SQL Server focuses on making I/O highly efficient. Buffer management is a key component in achieving this efficiency. The buffer management component consists of two mechanisms: the buffer manager to access and update database pages, and the buffer cache (also called the buffer pool), to reduce database file I/O.

How buffer management works

A buffer is an 8 KB page in memory, the same size as a data or index page. Thus, the buffer cache is divided into 8 KB pages. The buffer manager manages the functions for reading data or index pages from the database disk files into the buffer cache and writing modified pages back to disk. A page remains in the buffer cache until the buffer manager needs the buffer area to read in more data. Data is written back to disk only if it is modified. Data in the buffer cache can be modified multiple times before being written back to disk. For more information, see Reading Pages and Writing Pages.

When SQL Server starts, it computes the size of virtual address space for the buffer cache based on a number of parameters such as the amount of physical memory on the system, the configured number of maximum server threads, and various startup parameters. SQL Server reserves this computed amount of its process virtual address space (called the memory target) for the buffer cache, but it acquires (commits) only the required amount of physical memory for the current load. You can query the bpool_commit_target and bpool_committed columns in the sys.dm_os_sys_info catalog view to return the number of pages reserved as the memory target and the number of pages currently committed in the buffer cache, respectively.

The interval between SQL Server startup and when the buffer cache obtains its memory target is called ramp-up. During this time, read requests fill the buffers as needed. For example, a single 8 KB page read request fills a single buffer page. This means the ramp-up depends on the number and type of client requests. Ramp-up is expedited by transforming single page read requests into aligned eight page requests (making up one extent). This allows the ramp-up to finish much faster, especially on machines with a lot of memory. For more information about pages and extents, refer to Pages and Extents Architecture Guide.

Because the buffer manager uses most of the memory in the SQL Server process, it cooperates with the memory manager to allow other components to use its buffers. The buffer manager interacts primarily with the following components:

- Resource manager to control overall memory usage and, in 32-bit platforms, to control address space usage.

- Database manager and the SQL Server Operating System (SQLOS) for low-level file I/O operations.

- Log manager for write-ahead logging.

Supported Features

The buffer manager supports the following features:

The buffer manager is non-uniform memory access (NUMA) aware. Buffer cache pages are distributed across hardware NUMA nodes, which allows a thread to access a buffer page that is allocated on the local NUMA node rather than from foreign memory.

The buffer manager supports Hot Add Memory, which allows users to add physical memory without restarting the server.

The buffer manager supports large pages on 64-bit platforms. The page size is specific to the version of Windows.

Note

Prior to SQL Server 2012 (11.x), enabling large pages in SQL Server requires trace flag 834.

The buffer manager provides additional diagnostics that are exposed through dynamic management views. You can use these views to monitor a variety of operating system resources that are specific to SQL Server. For example, you can use the sys.dm_os_buffer_descriptors view to monitor the pages in the buffer cache.

Disk I/O

The buffer manager only performs reads and writes to the database. Other file and database operations such as open, close, extend, and shrink are performed by the database manager and file manager components.

Disk I/O operations by the buffer manager have the following characteristics:

- All I/Os are performed asynchronously, which allows the calling thread to continue processing while the I/O operation takes place in the background.

- All I/Os are issued in the calling threads unless the affinity I/O option is in use. The affinity I/O mask option binds SQL Server disk I/O to a specified subset of CPUs. In high-end SQL Server online transactional processing (OLTP) environments, this extension can enhance the performance of SQL Server threads issuing I/Os.

- Multiple page I/Os are accomplished with scatter-gather I/O, which allows data to be transferred into or out of noncontiguous areas of memory. This means that SQL Server can quickly fill or flush the buffer cache while avoiding multiple physical I/O requests.

Long I/O requests

The buffer manager reports on any I/O request that has been outstanding for at least 15 seconds. This helps the system administrator distinguish between SQL Server problems and I/O subsystem problems. Error message 833 is reported and appears in the SQL Server error log as follows:

SQL Server has encountered ## occurrence(s) of I/O requests taking longer than 15 seconds to complete on file [##] in database [##] (#). The OS file handle is 0x00000. The offset of the latest long I/O is: 0x00000.

A long I/O may be either a read or a write; it is not currently indicated in the message. Long-I/O messages are warnings, not errors. They do not indicate problems with SQL Server but with the underlying I/O system. The messages are reported to help the system administrator find the cause of poor SQL Server response times more quickly, and to distinguish problems that are outside the control of SQL Server. As such, they do not require any action, but the system administrator should investigate why the I/O request took so long, and whether the time is justifiable.

Causes of Long-I/O Requests

A long-I/O message may indicate that an I/O is permanently blocked and will never complete (known as lost I/O), or merely that it just has not completed yet. It is not possible to tell from the message which scenario is the case, although a lost I/O will often lead to a latch timeout.

Long I/Os often indicate a SQL Server workload that is too intense for the disk subsystem. An inadequate disk subsystem may be indicated when:

- Multiple long I/O messages appear in the error log during a heavy SQL Server workload.

- Perfmon counters show long disk latencies, long disk queues, or no disk idle time.

Long I/Os may also be caused by a component in the I/O path (for example, a driver, controller, or firmware) continually postponing servicing an old I/O request in favor of servicing newer requests that are closer to the current position of the disk head. The common technique of processing requests in priority based upon which ones are closest to the current position of the read/write head is known as 'elevator seeking.' This may be difficult to corroborate with the Windows System Monitor (PERFMON.EXE) tool because most I/Os are being serviced promptly. Long I/O requests can be aggravated by workloads that perform large amounts of sequential I/O, such as backup and restore, table scans, sorting, creating indexes, bulk loads, and zeroing out files.

Isolated long I/Os that do not appear related to any of the previous conditions may be caused by a hardware or driver problem. The system event log may contain a related event that helps to diagnose the problem.

Memory pressure detection

Memory pressure is a condition resulting from memory shortage, and can result in:

- Extra I/Os (such as very active lazy writer background thread)

- Higher recompile ratio

- Longer running queries (if memory grant waits exist)

- Extra CPU cycles

This situation can be triggered by external or internal causes. External causes include:

- Available physical memory (RAM) is low. This causes the system to trim working sets of currently running processes, which may result in overall slowdown. SQL Server may reduce the commit target of the buffer pool and start trimming internal caches more often.

- Overall available system memory (which includes the system page file) is low. This may cause the system to fail memory allocations, as it is unable to page out currently allocated memory.Internal causes include:

- Responding to the external memory pressure, when the SQL Server Database Engine sets lower memory usage caps.

- Memory settings were manually lowered by reducing the max server memory configuration.

- Changes in memory distribution of internal components between the several caches.

The SQL Server Database Engine implements a framework dedicated to detecting and handling memory pressure, as part of its dynamic memory management. This framework includes the backgroud task called Resource Monitor. The Resource Monitor task monitors the state of external and internal memory indicators. Once one of these indicators changes status, it calculates the corresponding notification and it broadcasts it. These notifications are internal messages from each of the engine components, and stored in ring buffers.

Two ring buffers hold information relevant to dynamic memory management:

- The Resource Monitor ring buffer, which tracks Resource Monitor activity like was memory pressure signaled or not. This ring buffer has status information depending on the current condition of RESOURCE_MEMPHYSICAL_HIGH, RESOURCE_MEMPHYSICAL_LOW, RESOURCE_MEMPHYSICAL_STEADY, or RESOURCE_MEMVIRTUAL_LOW.

- The Memory Broker ring buffer, which contains records of memory notifications for each Resource Governor resource pool. As internal memory pressure is detected, low memory notification is turned on for components that allocate memory, to trigger actions meant to balance the memory between caches.

Memory brokers monitor the demand consumption of memory by each component and then based on the information collected, it calculates and optimal value of memory for each of these components. There is a set of brokers for each Resource Governor resource pool. This information is then broadcast to each of the components, which grow or shrink their usage as required.For more information about memory brokers, see sys.dm_os_memory_brokers.

Error Detection

Database pages can use one of two optional mechanisms that help insure the integrity of the page from the time it is written to disk until it is read again: torn page protection and checksum protection. These mechanisms allow an independent method of verifying the correctness of not only the data storage, but hardware components such as controllers, drivers, cables, and even the operating system. The protection is added to the page just before writing it to disk, and verified after it is read from disk.

SQL Server will retry any read that fails with a checksum, torn page, or other I/O error four times. If the read is successful in any one of the retry attempts, a message will be written to the error log and the command that triggered the read will continue. If the retry attempts fail, the command will fail with error message 824.

Windows Server Memory Architecture

The kind of page protection used is an attribute of the database containing the page. Checksum protection is the default protection for databases created in SQL Server 2005 (9.x) and later. The page protection mechanism is specified at database creation time, and may be altered by using ALTER DATABASE SET. You can determine the current page protection setting by querying the page_verify_option column in the sys.databases catalog view or the IsTornPageDetectionEnabled property of the DATABASEPROPERTYEX function.

Note

If the page protection setting is changed, the new setting does not immediately affect the entire database. Instead, pages adopt the current protection level of the database whenever they are written next. This means that the database may be composed of pages with different kinds of protection.

Torn Page Protection

Torn page protection, introduced in SQL Server 2000, is primarily a way of detecting page corruptions due to power failures. For example, an unexpected power failure may leave only part of a page written to disk. When torn page protection is used, a specific 2-bit signature pattern for each 512-byte sector in the 8-kilobyte (KB) database page and stored in the database page header when the page is written to disk. When the page is read from disk, the torn bits stored in the page header are compared to the actual page sector information. The signature pattern alternates between binary 01 and 10 with every write, so it is always possible to tell when only a portion of the sectors made it to disk: if a bit is in the wrong state when the page is later read, the page was written incorrectly and a torn page is detected. Torn page detection uses minimal resources; however, it does not detect all errors caused by disk hardware failures. For information on setting torn page detection, see ALTER DATABASE SET Options (Transact-SQL).

Checksum Protection

Checksum protection, introduced in SQL Server 2005 (9.x), provides stronger data integrity checking. A checksum is calculated for the data in each page that is written, and stored in the page header. Whenever a page with a stored checksum is read from disk, the database engine recalculates the checksum for the data in the page and raises error 824 if the new checksum is different from the stored checksum. Checksum protection can catch more errors than torn page protection because it is affected by every byte of the page, however, it is moderately resource intensive. When checksum is enabled, errors caused by power failures and flawed hardware or firmware can be detected any time the buffer manager reads a page from disk. For information on setting checksum, see ALTER DATABASE SET Options (Transact-SQL).

Important

Windows Ce 6.0 Memory Architecture

When a user or system database is upgraded to SQL Server 2005 (9.x) or a later version, the PAGE_VERIFY value (NONE or TORN_PAGE_DETECTION) is retained. We recommend that you use CHECKSUM.TORN_PAGE_DETECTION may use fewer resources but provides a minimal subset of the CHECKSUM protection.

Understanding Non-uniform Memory Access

SQL Server is non-uniform memory access (NUMA) aware, and performs well on NUMA hardware without special configuration. As clock speed and the number of processors increase, it becomes increasingly difficult to reduce the memory latency required to use this additional processing power. To circumvent this, hardware vendors provide large L3 caches, but this is only a limited solution. NUMA architecture provides a scalable solution to this problem. SQL Server has been designed to take advantage of NUMA-based computers without requiring any application changes. For more information, see How to: Configure SQL Server to Use Soft-NUMA.

Memory Architecture Pdf

See Also

Windows Memory Architecture Pdf

Server Memory Server Configuration Options

Reading Pages

Writing Pages

How to: Configure SQL Server to Use Soft-NUMA

Requirements for Using Memory-Optimized Tables

Resolve Out Of Memory Issues Using Memory-Optimized Tables